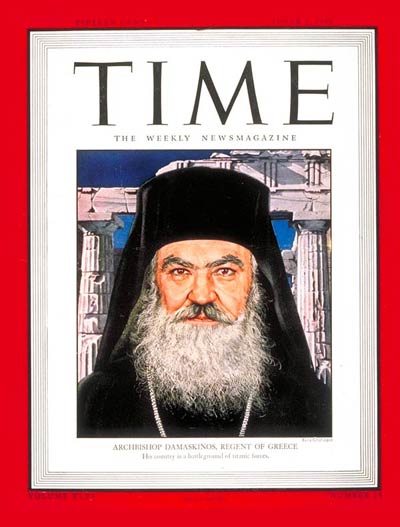

Archbishop

Damaskinos Papandreou was born Dimitrios Papandreou in Dorvitsa,

Greece in 1890. He enlisted in the Greek army during the Balkan Wars.

Ordained a priest of the Greek Orthodox Church in 1917, he was

appointed archbishop of Athens in 1941.

During the Holocaust, Archbishop

Damaskinos and Athens police chief Angelos Evert saved thousands of

Greek Jews.

Although an estimated 87% of the

nation’s Jewish population — 60,000 to 70,000 Greek Jews — perished

during the Holocaust, 10,000 survived, largely due to the Greek

people’s refusal to cooperate with German plans for deportations.

With the arrival of the Axis

occupation, deportations from cities like the northern port of

Thessaloniki proceeded at a rapid pace. Many Jews fleeing

persecution in the north found a safe haven in Athens.

On September 20, 1943, Dieter

Wisliceny — a deputy of Adolph Eichmann, the administrator of the

Nazi Final Solution — arrived in Athens. Wisliceny ordered Chief

Rabbi Elias Barzilai to appear before him, to provide accurate

figures about the Jewish population in Athens and to create a

Judernat. Made up of Jews who were coerced into joining, a Judernat

made compliant Jews ”responsible” for keeping law and order in a

Jewish community, and used them as a liaison between the German

authorities and the Jewish population.

Wisliceny ordered Barzilai to provide

the names and address of all members of Athens’ Jewish community,

the names of all foreign Jews living in the area, the names of

Italian Jews in Athens, and the names of those who had assisted Jews

who had escaped to Palestine. He also commanded Barzilai to compile

a list of individuals willing to serve on a new council — of which

Barzilai was to be president — that would create a Jewish police

force to carry out Nazi demands; and unveiled plans to create

identity cards for all of Athens’ Jewish population.

Shaken by his encounter with the Nazi

commander, the Rabbi contacted Archbishop Damaskinos and told him

about the meeting.

Since Damaskinos knew what had taken

place in the north, he suggested that the entire Jewish community

should take flight, because it couldn’t be protected.

Rabbi Barzilai asked the Germans for

more time to compose the requested lists, and then, after meeting

with other leaders of the Jewish community, he destroyed the

community records and advised the Jewish people to flee. A few days

later, the Rabbi himself left the capital and joined the resistance.

The Church of Greece, under

Damaskinos’ leadership, condemned Hitler’s plans for the country and

instructed priests to announce its position in their sermons.

Jews had participated freely with

other Greeks in all walks of life for 2,300 years, co-existing in

harmony with their Orthodox countrymen, contributing good work in

numerous fields. Jews had lived in Athens since the time of

Alexander the Great, in the mid-fourth century, many having sought

sanctuary in Greece after having been expelled from Spain in 1492.

During the Holocaust, the Greek Jewish population was almost

completely destroyed.

As they prepared to implement the

deportation and mass murder of their Final Solution, the Nazis

compiled intelligence reports about the Jewish population of Athens.

They chose important Jewish holidays for their monstrous acts,

beginning with an order on the eve of Yom Kippur, signed by the

German military commander in Athens, S.S. General Jurgen Stroop,

which organized the city’s Jewish community under Nazi supervision.

The Jewish population in Athens had

increased since the outbreak of the war. Damaskinos’ and the Rabbi’s

work had transformed the city in a safe refuge. Since many of the

newly arrived Jews had no fixed place of residence, German

intelligence about the Jewish population was often wrong.

Under the order issued by Stroop,

Jews were commanded to appear at community offices within five days

to declare their residences and register their names. Despite the

threat of dire consequences for failing to appear, only 200 showed

up.

In a similar instance, the German

authorities announced that they were planning to bring a special

flour to Athens for Passover, so the Jewish population could prepare

matzoh — provided they were willing to reveal themselves and

register with the authorities. Although the false act of kindness

tempted some, many more Jews registered because they were afraid the

Nazis would enact reprisals on their Christian neighbors, who had

been shielding them from the persecution.

When the Germans started rounding up

Jews, over 600 Greek Orthodox priests were arrested and deported

because of their actions in helping Jews, and many Jews were saved

by the Greek police, the clergy and the resistance. Damaskinos and

Evert faced the threat of death for their efforts, and would surely

have been killed if the extent of their assistance had become known

to the Germans.

There were several means of escape.

Many left by boat from Oropos in Attica, where they were frequently

forced to pay enormous fees for a three week journey to Turkey. Some

young men without families escaped to partisan camps in the

mountains. False baptismal certificates and new identity papers from

the Greek Orthodox Church would also help a desperate fleeing Jew.

Archbishop Damaskinos oversaw the

creation of several thousand such certificates, and Athens police

chief Evert provided more than 27,000 false identify papers to

desperate Jews seeking protection from the Nazis.

The Archbishop also ordered

monasteries and convents in Athens to shelter Jews, and urged his

priests to ask their congregations to hide the Jews in their homes.

As a result, more than 250 Jewish children were hidden by Orthodox

clergy alone.

When all official appeals to stop the

deportations failed, Archbishop Damaskinos spearheaded a direct

appeal to the Germans, in the form of a letter composed by the

famous Greek poet Angelos Sikelianos and signed by prominent Greek

citizens, in a bold attempt to appeal to the hearts and minds of the

occupying authorities, in defense of the Jews who were being

persecuted.

The letter incited the rage of the

Nazi general Stroop, who threatened the Archbishop with death by a

firing squad. Damaskinos’ response was, ”Greek religious leaders are

not shot, they are hanged. I request that you respect this custom.”

The simple courage of the religious leader’s reply caught the Nazi

commander off guard, and his life was spared.

The appeal of the Archbishop and his

fellow Greeks is unique; there is no similar document of protest of

the Nazis during World War II that has come to light in any other

European country. It reads, in part:

”The Greek Orthodox Church and

the Academic World of Greek People Protest against the

Persecution… The Greek people were… deeply grieved to learn that

the German Occupation Authorities have already started to put

into effect a program of gradual deportation of the Greek Jewish

community… and that the first groups of deportees are already on

their way to Poland…”

”According to the terms of the

armistice, all Greek citizens, without distinction of race or

religion, were to be treated equally by the Occupation

Authorities. The Greek Jews have proven themselves… valuable

contributors to the economic growth of the country [and]

law-abiding citizens who fully understand their duties as

Greeks. They have made sacrifices for the Greek country, and

were always on the front lines of the struggle of the Greek

nation to defend its inalienable historical rights…”

”In our national consciousness,

all the children of Mother Greece are an inseparable unity: they

are equal members of the national body irrespective of religion…

Our holy religion does not recognize superior or inferior

qualities based on race or religion, as it is stated: ‘There is

neither Jew nor Greek’ and thus condemns any attempt to

discriminate or create racial or religious differences. Our

common fate both in days of glory and in periods of national

misfortune forged inseparable bonds between all Greek citizens,

without exemption, irrespective of race…”

”Today we are… deeply concerned

with the fate of 60,000 of our fellow citizens who are Jews… we

have lived together in both slavery and freedom, and we have

come to appreciate their feelings, their brotherly attitude,

their economic activity, and most important, their indefectible

patriotism…”

During World War II, Greece lost

580,000 of its pre-war population of 6.5 million, and an additional

100,000 Greeks were wounded in the fighting. Ordinary Greeks put

themselves in mortal danger, protesting against the occupation

authorities. In the case of Athens’ Jewish population, assimilation

and a strong resistance movement helped at least some Jewish Greeks

to survive the Nazi onslaught.

Five thousand Jews remain in Athens,

helping to rebuild Jewish life in post-war Greece. The Greek

government sees Jewish heritage as part of the country’s national

heritage, and has refurbished the Jewish Museum of Greece in Athens.

An honored site among the nation’s many historic treasures, the

oldest synagogue site in Greece is a ruin from the Fifth Century

B.C.E., located in Athens’ ancient marketplace, the agora at the

foot of the Acropolis.

After the war, Archbishop Damaskinos

served as regent of Greece until King Georgios II returned from

exile. When fighting broke out between pro-royalist Greek soldiers

and communist partisans in 1945, the Archbishop was appointed Prime

Minister. He called for peace and order in the country. He

relinquished his leadership position when the king was formally

recalled in 1946.

Archbishop Damaskinos died in Athens

on May 20, 1949.

BIBLIOGRAPHY