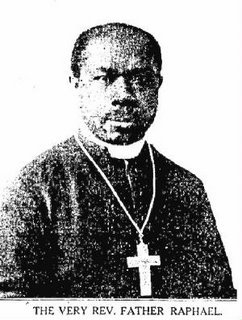

Very Rev.

Raphael Morgan (born Robert Josias Morgan,

186* / 187* to 19**) was a Jamaican-American

priest of the

Ecumenical Patriarchate, designated as "Priest-Apostolic"

(Greek: Éåñáðïóôïëïò) to America and the West

Indies,[note

1][1]

later the founder and superior of the Order

of the Cross of

Golgotha,[note

2] and thought to be the first Black

Orthodox clergyman in America.

He spoke

broken Greek, and therefore served mostly in

English. Having recently been discovered, his

life has garnered great interest, but much of

his life still remains shrouded in mystery.

Fr. Raphael is

said to have resided all over the world,

including: "in Palestine, Syria, Joppa, Greece,

Cyprus, Mytilene, Chios, Sicily, Crete, Egypt,

Russia, Ottoman Turkey, Austria, Germany,

England, France, Scandinavia, Belgium, Holland,

Italy, Switzerland, Bermuda, and the United

States."[2]

Early Life

Robert Josias

Morgan was born in Chapelton, Clarence Parish,

Jamaica either in the late 1860s or early 1870s

to Robert Josias and Mary Ann (née Johnson)

Morgan. He was born six months after his

father's death, and named in his honour. Robert

was raised in the Anglican tradition and was

received elementary schooling locally.[2]

In his teenage

years he travelled to Colón, Panama, then to

British Honduras, back to Jamaica, and then to

the United States. He became a minister in the

African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) and

left as a

missionary to Germany.[2]

Period in the Church

of England

He then came

to England, where he joined the

Church of England and was sent to Sierra

Leona to the

Church Missionary Society Grammar School at

Freetown. He studied Greek, Latin, and other

higher-level subjects. Being poor, Robert had to

work to support himself, and worked as second

master of a public school in Freetown. He took

course in the Church Missionary Society

College at Fourah Bay in Freetown, and was

soon appointed a missionary teacher and

lay-reader by the Episcopalian

Bishop of Liberia, the Right Reverend

Samuel David Ferguson.[2]

Robert later said during a trip to Jamaica in

1901 that he served five years in West Africa,

of which he spent three years in missionary work.[3]

After this

Robert again visited England for private study,

and then travelled to America to work amongst

the African-American community as a lay-reader.

He was accepted as a Postulant and as candidate

for the Episcopalian

deaconate. During the canonical period of

waiting period before ordination, Robert again

returned to England to study at Saint Aidan's

Theological College in

Birkenhead, and finally prosecuted his

studies at

King's College of the University of London.[2]

The colleges however do not contain records of

his attendance. [note

3]

Period in the

Episcopal Church

He returned to

America, and on

June 20, 1895 was

ordained as

deacon [note

4] by the Rt. Rev.

Leighton Coleman,[4]

Bishop of the

Episcopalian Diocese of Delaware, and a well-known

opponent of racism. Robert was appointed

honorary curate in St Matthews' Church in

Wilmington, Delaware, serving there from 1896 to

1897,[5]

and procured a job as a teacher for a few public

schools in Delaware. From 1897 he served at

Charleston, West Virginia.[5]

In 1898, the

deacon Robert (Rev. R.J. Morgan) was transferred

to the Missionary Jurisdiction of Ashville (now

in the

Diocese of Western North Carolina). By 1899

he was listed as being assistant minister at

St. Stephen's Chapel in Morganton, North

Carolina, and

St. Cyprian's Church in Lincolnton, North

Carolina.[6][note

5]

In 1901-1902

Rev. R. J. Morgan made a visit to his homeland

Jamaica. In October 1901 he gave an address to

the Jamaica Church Missionary Union, on West

Africa and mission work.[3]

He also gave a lecture in

Port Maria, Jamaica in October 1902,

entitled "Africa - lts people, Tribes,

Idolatry, Customs."[7]

Between 1900

and 1906, Robert moved around much of the

Eastern seaboard. From 1902 to 1905 Deacon

Morgan served at Richmond, Virginia; in 1905 at

Nashville, Tennessee; and by 1906 at

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania with his address care

of the

Church of the Crucifixion.[5][note

6]

At some point

during this period he joined an offshoot of the

Episcopalian Church, known as the "American

Catholic Church" (ACC), a sect

founded by

Joseph René Vilatte.[note

7] He is listed in the records of the

Episcopal Church of the USA as late as 1908,

when he was suspended from ministry on the

allegations of abandoning his post.

Orthodoxy

Trip to Russia

By the turn of

the 20th century, Robert seriously began to

question his faith, and began intensive study of

Anglicanism, Catholicism, and Orthodoxy over a

three year period, to discover what he felt was

the true religion. He concluded that the

Orthodox Church was "the pillar and ground of

truth", resigned from the Episcopalian Church,

and embarked on an extensive trip abroad

beginning in the

Russian Empire in 1904.[2]

Once there,

Robert visited various

monasteries and churches, including sites in

Odessa, St. Petersburg, Moscow and

Kiev, soon becoming quite the sensation.

Sundry periodicals began publishing pictures and

articles on him, and soon Robert became the

Special Guest of the Tsar. He was allowed to be

present for the anniversary celebrations of

Nicholas II's coronation, and the

memorial service said for the repose of the

soul of the late Emperor Alexander III.[8]

Leaving

Russia, Robert traveled Turkey, Cyprus, and the

Holy Land, returning to America and writing

an article to the Russian-American Orthodox

Messenger (Vestnik) in 1904 about his

experience in Russia. In this open letter,

Morgan expressed hope that the Anglican Church

could unite with the Orthodox Churches, clearly

moved by his experience in Russia.[note

8] People of African descent were

generally well-received within the Russian

Empire, Morgan believed.

Abram Hannibal had served under Emperor

Peter the Great, and rose to lieutenant general

in the Russian Army. Visiting artists, foreign

service officials, and athletes, such as famous

horse jockey

Jimmy Winkfield, were likewise welcomed.

With his experience of Russia and Russian

Orthodoxy fresh in his mind, Morgan returned to

the United States and continued his spiritual

quest.[9]

Study and Trip to

Ecumenical Patriarchate

For another

three years, Robert studied under Greek priests

for his

baptism,[2]

eventually deciding to seek entry and ordination

in the

Greek Orthodox Church. In January of 1906,

he is documented as assisting in the

Christmas

liturgy.[note

9] In 1907 the Philadephia Greek

community referred Robert to the

Ecumenical Patriarchate in Constantinople

armed with two letters of support. One was a

recommendation from Fr. Demetrios Petrides, the

Greek priest then serving the Philadelphia

community, dated

18 June 1907, who described Morgan as a man

sincerely coming into Orthodoxy after long and

diligent study, and recommending his baptism and

ordination into the priesthood. The second

letter of support was from the "Ecclesiastical

Committee" of the Philadelphia Greek Orthodox

Church, stating he could serve as an assistant

priest if he failed to form a separate Orthodox

parish among his fellow Black Americans.[note

10]

In

Constantinople, Robert was interviewed by

Metropolitan

Joachim (Phoropoulos) of Pelagonia, one of

the few bishops of the

Ecumenical Patriarchate that could speak

English and among the most learned of the

Constantinopolitan hierarchs of that time.

Metropolitan Joachim examined Robert, noting

that he had a "deep knowledge of the

teachings of the Orthodox Church", and that

he also had a certificate from the President of

the Methodist Community, duly notarized, stating

that he was a man "of high calling and of a

religious life".[10]

Citing the Biblical exhortation "...the one

who comes to Me I will certainly not cast out"

(John 6:37), the

metropolitan concluded that Robert should be

baptised,

chrismated,

ordained, and sent back to America in order

to "carry the light of the Orthodox faith

among his racial brothers".

Baptism and Ordination

On Friday

August 2, 1907 the

Holy Synod approved that the

Baptism take place the following Sunday in

the Church of the Lifegiving Source at

the Patriarchal Monastery at Valoukli, in

Constantinople.[note

11] Metropolitan

Joachim (Phoropoulos) of Pelagonia was to

officiate at the sacrament, and the

sponsor was to be Bishop Leontios (Liverios)

of Theodoroupolis, Abbott of the Monastery at

Valoukli. On Sunday August 4, 1907, Robert was

baptised "Raphael" before 3000 people;[2]

subsequently he was ordained a

deacon on

August 12, 1907 by Metropolitan Joachim; and

finally ordained a

priest on the feast of the

Dormition of the

Theotokos,

August 15, 1907.[note

12] According to the contemporary

Uniate periodical L'Echo d' Orient,

which sarcastically described Morgan's Baptism

of triple immerson, the Metropolitan conducted

the sacraments of Baptism and Ordination in the

English language, following which Fr. Raphael

chanted the

Divine Liturgy in English.[11]

Fr. Raphael Morgan's conversion to the Greek

Orthodox Church made him the first African

American Orthodox priest.

Fr. Raphael

was sent back to America with vestments, a

cross, and 20 pounds sterling for his

traveling expenses. He was allowed to hear

confessions, but denied

Holy Chrism and an

antimension, presumably to attach his

missionary ministry to the Philadelphia church.

The minutes of the Holy Synod from

October 2, 1907, made it clear in fact that

Fr. Raphael was to be under the jurisdiction of

Rev. Petrides of Philadelphia, until such time

as he had been trained in liturgics and was able

to establish a separate Orthodox parish.[10]

Return to America

Ellis Island

records indicate the arrival in New York from

Naples, Italy, of the priest, Raffaele Morgan,

in December 1907.[12]

Once home, Fr. Raphael baptized his wife and

children in the Orthodox Church. This is noted

in the minutes of the Holy Synod of

February 9, 1908, which acknowledges receipt

of a communication from Fr. Raphael.

The last

mention of Fr. Raphael in Patriarchal records is

in the minutes of the Holy Synod of

November 4, 1908, which cite a letter from

Fr. Raphael recommending an Anglican priest of

Philadelphia, named "A.C.V. Cartier",[note

13] as a candidate for conversion to

Orthodoxy and ordination as a priest. Cartier

was rector of the

African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, in

Philadelphia, from 1906-12.[note

14] Saint Thomas' served the African

American elite of Philadelphia and was one of

the most prestigious congregations in African

American Christianity, having been started in

1794 by

Absalom Jones, one of the founders, together

with

Richard Allen, of the

African Methodist Episcopal Church.[13]

According to the letter, Cartier desired as an

Orthodox priest to undertake missionary work

among his fellow blacks. Due to the fact that

the jurisdiction over the Greek Church of the

diaspora had been ceded by the Ecumenical

Patriarchate to the

Church of Greece in 1908, the request was

forwarded there. However according to

Greek-American historian Paul G. Manolis, a

search of the Archives of the Holy Synod of the

Church of Greece did not turn up any

correspondence with Fr. Raphael. His letter

about A.C.V. Cartier is the only indication we

have from Church records of his missionary

efforts among his people.[10]

In 1909, his

wife filed for divorce, on the alleged charges

of cruelty and failure to support their

children. She left with their son Cyril to

Delaware County, where she remarried.

Monastic Tonsure

In 1911 Fr.

Raphael sailed to Cyprus, presumably to be

tonsured a

hieromonk. Possibly somewhere around this

time, he founded the Order of the Cross of

Golgotha (O.C.G.).[note

2] However, Fr. Oliver Herbel (AOC)

has suggested that in 1911 Fr. Raphael was

tonsured in Athens.[14]

As is noted above however, the Archives of the

Holy Synod of the

Church of Greece contain no information

about Fr. Raphael.

Lecture Tour in

Jamaica

The Jamaica

Times article of

April 26, 1913, wrote that Fr. Raphael was

headquartered at Philadelphia where he wanted to

build a chapel for his missionary efforts, that

he had recently visited Europe to collect funds

to this end, and had the intention of extending

his work to the West Indies.[15]

Near the end

of 1913, Fr. Raphael visited his homeland of

Jamaica, staying for several months until

sometime the next year. While there, he met a

group of Syrians, who were complaining of a lack

of Orthodox churches on the island. Fr. Raphael

did his best to contact the Syrian-American

diocese of the Russian church, writing to St

Raphael of Brooklyn, but as most of their

descendants are now communicants in the

Episcopal Church, this presumably came to no

avail. In December, a Russian warship came to

port, and he concelebrated the

Divine Liturgy with the sailors, their

chaplain, and his new-found Syrians.

The main work

of his visit, however, was a lecture circuit

that he ran throughout Jamaica. Citing a lack of

Orthodox churches, Fr. Raphael would speak at

churches of various denominations. The topics

would usually cover his travels, the Holy Land,

and Holy Orthodoxy. At some point, he even made

it to his hometown of Chapelton, to whom he

remarked of his name change, "I will always

be Robert to you".[16]

According to

the Daily Gleaner edition of

November 2, 1914, Fr. Raphael had just set

sail back for America to start mission work

under his Faith.[note

15]

Last Known Records

In 1916 Fr.

Raphael was still in Philadelphia, having made

the Philadelphia Greek parish his base of

operations.[17]

The last documentation of Fr. Raphael comes from

a letter to the Daily Gleaner on

October 4, 1916. Representing a group of

about a dozen other like-minded

Jamaican-Americans, he wrote in to protest the

lectures of Black Nationalist Marcus Garvey.[note

16] Garvey's views on Jamaica, they

felt, were damaging to both the reputation of

their homeland and its people, enumerating

several objections to Garvey's stated preference

for the prejudice of the American whites over

that of English whites.[9]

Garvey's response came ten days later, in which

he called the letter a conspiratorial

fabrication meant to undermine the success and

favour he had gained while in Jamaica and in the

United States.

Little is

known of Fr. Raphael's life after this point,

except from some interviews conducted in the

1970s between Greek-American historian Paul G.

Manolis and surviving members of the

Greek Community of the Annunciation in

Philadelphia, who recalled the black priest who

was evidently a part of their community for a

period of time. One elderly woman, Grammatike

Kritikos Sherwin, remembered that Fr Raphael's

daughter left to attend Oxford; another

parishioner, Kyriacos Biniaris, recalls that

Morgan, whose hand "he kissed many times", spoke

broken Greek and served with Fr. Petrides

reciting the liturgy mostly in English; whilst

another, a George Liacouras, recalled that after

serving in Philadelphia for some years, Fr.

Raphael left for Jerusalem, never to return.[note

17][10]

The

Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America has no

record either of Fr. Raphael Morgan, nor of Fr.

Demetrios Petrides, as the first records for the

Philadelphia community in the archives only

began in 1918.

Influence

"Indirect Conversion

of Thousands" Theory

During the

16th Annual Ancient Christianity and

African-American Conference in 2009, Matthew

Namee presented a 23-minute lecture on the

heretofore recently discovered life of Fr.

Raphael Morgan. He postulated that even if Fr.

Raphael's missionary efforts failed outside of

his immediate family, he may be indirectly

responsible for the conversion of thousands, via

contact with Episcopal priest

George Alexander McGuire (1866-1934).

Fr. Raphael

and George McGuire

Namee questions whence the idea came for McGuire

to form namely an Orthodox church. Fr.

Raphael Morgan and George McGuire had some

striking similarities, including the facts that

both:

-

served

concurrently or consecutively at

St Philip's Episcopal Church in

Virginia,[note

18]

-

were

ordained in the Episcopal Church around the

same time,[note

19] and

-

both

later served in Philadelphia, each having

had some contact with Rev. A.C.V. Cartier of

the

African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas.

Namee

concludes that with so many coincidences, it is

impossible for these two men to not have known

one another; and therefore it must be from some

influence - either in conversation with Fr.

Raphael or through evangelism - that McGuire

received his inspiration and came to know the

Orthodox Church.

An additional

point is that Garvey already knew of Fr. Raphael

when McGuire joined his organization in 1920

(since Fr. Raphael had written the letter in

1916 protesting Garvey's lectures), which makes

it likely that McGuire and Garvey had discussed

Morgan at some point.

One deterrent

from this theory comes in the familiarity that

McGuire had with the Orthodox Church by his

consecrator, Joseph René Vilatte.[note

20] At various points, Vilatte come

into contact with both the

Russian and

Syriac Orthodox Churches in a move for

Catholic-Orthodox reconciliation, having even

been accepted for a while by Bishop

Vladimir of

Alaska in May of 1891.

African

Orthodox Church

George McGuire became an associate of Marcus

Garvey and his Black Nationalist

UNIA movement, being appointed the first

Chaplain-General of the organization at its

inaugural international convention in New York

in August 1920. On September 28, 1921, he was

made a bishop of the American Catholic Church by

Joseph René Vilatte, and soon after founded

the

African Orthodox Church, a non-canonical

Black Nationalist church, in the Anglican

tradition. Today, it is best known for its

canonisation of Jazz legend John Coltrane.

Bishop George

McGuire soon spread his African Orthodox Church

throughout the United States, and soon even made

a presence on the African continent in such

countries as

Uganda,

Kenya, and

Tanzania. Between 1924-1934 McGuire built

the AOC into a thriving international church.

Branches were eventually established in Canada,

Barbados, Cuba, South Africa, Uganda, Kenya,

Miami, Chicago, Harlem, Boston, Cambridge

(Massachusetts), and elsewhere. The official

organ of AOC, The Negro Churchman, became

an effective link for the far-flung

organization.[13]

However, around the time of the Second World

War, the African churches were cut off from the

American and in the post-war period had drifted

far enough way to request and come under the

omophorion of the

Church of Alexandria. Thus in 1946 the Holy

Synod of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of

Alexandria and all Africa officially recognized

and received the "African Orthodox Church" in

Kenya and Uganda.[note

21]

Legacy

Scholar Gavin

White, writing in the 1970's, states that if

Morgan tried to organize an African-American

Greek Orthodox church in Philadelphia, its

memory has vanished, and nothing whatsoever is

known about Morgan in later years. However he

hastens to add that:

-

"...there

can be no doubt that McGuire knew all about

Morgan and it is very probable that he knew

him personally. It is just possible that it

was Morgan who first introduced McGuire to

the Episcopal Church in Wilmington; it was

almost certainly Morgan who introduced

McGuire to the idea of Eastern episcopacy.[5]

This concurs

with Matthew Namee's conclusion above, that it

was Fr. Raphael who was George Alexander

McGuire's inspiration to form namely an "Orthodox"

church. In time the African-based portion of

McGuire's "African Orthodox Church" in

Kenya and Uganda, eventually did end up under

the canonical jurisdiction of the

Patriarchate of Alexandria and All Africa in

1946. And although those two churches were

already upon their own set path towards full

canonical Orthodoxy, McGuire was an important

part of that process at one stage, and Fr.

Raphael Morgan in turn, was behind McGuire's

inspiration to form an "Orthodox" church. In

this regard, by planting the seed, it can be

said that Fr. Raphael was also in some small

measure, indirectly or incidentally, a part of

that process in Africa as well.[note

22]

In the end,

while Fr. Raphael Morgan's work among Jamaicans

in Philadelphia appears to have been transitory,

nevertheless he did serve as an important

precedent for current African American interest

in Orthodoxy, especially that of Father

Moses Berry, director of the

Ozarks African American Heritage Museum, who

served as the priest to the

Theotokos, the “Unexpected Joy,” Orthodox

Mission (OCA)

in Ash Grove, Missouri.[9]

**********************************************

Notes

-

↑ According to Fr. Raphael's biography

in the Who's Who of the Colored Race,

1915, after he was ordained to the

priesthood:

-

"...at

a special service he was duly

commissioned

Priest-Apostolic from the Ecumenical

and Patriarchal Throne of Constantinople

to America and the West Indies." (Mather,

Frank Lincoln.

Who's Who of the Colored Race: A General

Biographical Dictionary of Men and Women of

African Descent. University of

Michigan. Gale Research Co., 1915. p.226.)

-

↑

2.0

2.1 The "Order of...",

could be any number of things including:

-

an

honorarium bestowed upon him for service

done in the Church;

-

an

entitling which lets others know of his

special mission in the Patriarchate/Diocese

etc.;

-

a

Society of monastics which transcends,

because of rare circumstances, physical

location;

-

it is

also possible that this was a monastic

brotherhood formed for Black Orthodox

Christians, since Morgan was referred to

as the “founder and superior” of

that religious fraternity, although the

formation of formal monastic orders is

not traditionally practiced in the

Orthodox tradition. The

Orthodox Church does not have

separate Orders (Franciscan, Carmelite

etc.) each with an entirely independent

rule/ethos of life. Despite being

mentioned on many occasions in association

with Morgan, no other material has ever been

found on the Order of the Cross of

Golgotha.

-

↑ It is possible that he academically

audited the courses, attending the classes

without receiving a formal grade.

-

↑ Fr. Raphael's name is given on a list

of Black Episcopal ordinations as follows:

"1895: Robert Josias Morgan, d. June 20,

Coleman; deposed; went abroad and was made a

priest in Greek Church." (Bragg, Rev.

George F. (D.D.). Chapter XXXVI: Negro

Ordinations from 1866 to the Present.

In:

History of the Afro-American group of the

Episcopal church (1922). Baltimore,

Md.: Church Advocate Press, 1922. p.273.)

-

↑ St. Cyprian's Episcopal Church was

established in 1886. The church once stood

on West Church in Lincolnton. The property

consisted of a church, a parsonage, and a

building used as a school. The church was

torn down during the 1970's. The church

remained primarily black and was not

integrated until 1979. (Jason L. Harpe.

Lincoln County Revisited.

Illustrated. Arcadia Publishing, 2003.

pg.18.)

-

↑ The

Church of the Crucifixion is the

second-oldest African-American congregation

in Pennsylvania (after the

African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas,

the oldest Black Episcopal congregation in

the country), the sixth oldest in the

country, and first Black parish formally

admitted into union with Convention in 1847.

A major Black cultural center in the late

19th and into the 20th Century, the Church

of the Crucifixion played many key roles in

African-American history for the City of

Philadelphia and the country.

-

↑ The "American Catholic Church"

(ACC) included the jurisdictions and groups

which had come out of

Joseph René Vilatte's Episcopal ministry

or were under his oversight. Among them were

French and English speaking constituencies,

and Polish and Italian ordinariates. The ACC

began on August 20, 1894, at a synod held in

Cleveland, Ohio, where Polish-speaking

parishes joined the jurisdiction of Bishop

Vilatte, however the ACC was actually

incorporated in July 1915.

-

↑ Upon Morgan's departure from Russia,

he wrote a letter, which was reprinted in

the October/November 1904 English supplement

to the Vestnik (Russian Orthodox

American Messenger, the official

publication of the

Russian Archdiocese in America. Here is

the text of that letter:

-

I,

Robert Josias Morgan, a legally

consecrated cleric of the American

Episcopal Church, find it necessary to

make it publicly known, that I am not a

Bishop, as it was announced in some

magazines and daily papers…

-

… I

am not a Bishop, but a legally

consecrated deacon. I came to Russia in

no way to represent anything, and I was

not sent by anybody. I came as a simple

tourist, chiefly with the object to see

the churches and the monasteries of this

country, to enjoy the ritual and the

service of the holy Orthodox Church,

about which I heard so much abroad. And

I am perfectly satisfied with everything

I saw and witnessed.

-

The

piety and the fear of God amongst the

Russian clergy, both superior and lower,

and of the lay people in general are too

great to be spoken of. I like Russia,

and as to the people I have simply grown

to love them for their gentleness, their

politeness, their amiability and

kindness. It would seem as if the

Christian religion penetrated the whole

life of the people. This can be observed

both in the private home life and the

social life. You have but to go to

Church in this country, and you

immediately see, that there is nothing

too valuable for the people to be

offered to God. Note how they pray, how

patiently they stand through the long

Church services…

-

Now,

having spent here about a month, I leave

your country with a feeling of profound

gratitude and take back to North America

all the good impressions I received

here. And when there I shall speak

boldly and loudly about the brotherly

feelings entertained here in the bosom

of the holy Orthodox Church towards its

Anglican sister of North America,

and about the prayers which are offered

here daily for the union of all the

Catholic Christendom.

-

My

constant humble prayer is for the union

of all Churches, and especially the

union of the Anglican faith with the

Orthodox

Church of Russia. I solicited the

Metropolitans and the Bishops to grant

me their blessing in regard to this

prayer and obtained it. Now I pray daily

and eagerly for a better mutual

understanding between the character and

their union. God grant a blessing to

this cause and a hearing to our prayers

and supplications. Let us solicit the

prayers of the Saints. Let us seek the

intercession of the holy

Mother of God. Virgin Mary, pray for

us!

In

conclusion I must say, that my stay in

Russia did me personally much good: I

feel now firmer and stronger spiritually

than I did before I came.

-

God

bless the Holy Catholic and Apostolic

Church of this country! God bless the

Emperor and all the reigning family! God

grant them a long life, peace and

prosperity!

-

I am

sincerely yours in God and in the name

of Mary,

-

Robert Josias Morgan.

(Matthew

Namee. "Robert

Josias Morgan visits Russia, 1904."

OrthodoxHistory.org (The Society for

Orthodox Chrisitan History in the Americas).

September 15, 2009.)

-

↑ The Philadelphia Inquirer

reported on

January 8, 1906, that “Rev. R.J.

Morgan of the American Catholic Church, an

off-shoot of the Protestant Episcopal

Church, assisted.”

-

↑ Summaries of the two letters are given

in the Synodal Minutes of

19 July, 1907, presided over by

Patriarch

Joachim III, who introduced the subject

of Morgan's baptism and ordination. As is

stated in the second letter, Morgan's goal

was to establish an Orthodox community of

Blacks ( "...íá ðçîç éäéáí ïñèïäïîïí

êïéíïôçôá ìåôáîõ ôùí åí Áìåñéêç ïìïöõëùí

áõôïõ Íéãñçôùí..." ).

-

↑ The Patriarchal Monastery at Valoukli

is where the cemetery with the graves of the

Patriarchs is found.

-

↑ In a letter from the Chief Archivist

of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, dated

April 4, 1973, it was confirmed that the

records of the Patriarchate show that Morgan

was baptized and renamed "Raphael".

(Manolis, Paul G. Raphael (Robert)

Morgan: The First Black Orthodox Priest in

America. Theologia: Epistēmonikon

Periodikon Ekdidomenon Kata Trimēnian.

(En Athenais: Vraveion Akadēmias Athēnōn),

1981, vol.52, no.3, pp.467.)

-

↑ A.C.V. Cartier was ordained to the

Episcopal deaconate by Bishop

Charles Quintard in 1895, and ordained

to the Episcopal priesthood in the same year

by Bishop Quintard. (Bragg, Rev. George F.

(D.D.). Chapter XXXVI: Negro Ordinations

from 1866 to the Present. In:

History of the Afro-American group of the

Episcopal church (1922). Baltimore,

Md.: Church Advocate Press, 1922. p.273.)

-

↑

George Alexander McGuire was rector of

The African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas

in Philadelphia from 1902-05. He was

succeeded as rector by A.C.V. Cartier

(1906-12), the man whom Morgan recommended

to the

Ecumenical Patriarchate for Orthodox

ordination.

-

↑ "Father Raphael, Priest of the

Greek Orthodox Church, who has been in the

island for some time, sailed for America

last week. It is understood that he will

return shortly to his native land and start

mission work under his Faith. As is well

known, the seat of the Greek Church to which

father Raphael belongs is not far from the

theatre of war, so there is no hope of the

Father returning to his Mother Church in a

hurry. Father Raphael is a native of

Clarendon." (The Daily Gleaner.

November 2, 1914. p.13.)

-

↑ Fr. Raphael signed the letter as

"Father Raphael, O.C.G., Priest-Apostolic,

the Greek-Orthodox Catholic Church."

Other signatories included: Dr. Uriah Smith,

Ernest P. Duncan, Ernest R. Jones, H.S.

Boulin, Phillip Hemmings, Joseph Vassal,

Henry H. Harper, S.C. Box, Aldred Campbell,

Hubert Barclay, John Moore, Victor Monroe,

Henry Booth, and many others. The full text

of the signed letter is printed in:

Robert A. Hill, Marcus Garvey, Universal

Negro Improvement Association. Letter

Denouncing Marcus Garvey. In:

The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro

Improvement Association Papers: 1826-August

1919. University of California Press,

1983. pp.196-197.

-

↑ If this is true, one possibility is

that Fr. Raphael remained with the monastic

Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulchre, of

the Greek Orthodox

Church of Jerusalem.

-

↑

St. Philip’s Episcopal Church of

Richmond, Virginia lists Morgan as having

been the rector of their parish for a short

time in 1901. He is listed as the rector

from “1901-April 1901.” Morgan’s predecessor

at St. Philip’s was a certain “Reverend

George Alexander McQuire,” who served

the parish from April 1898 to November 1900.

-

↑ Rev. Morgan was ordained to the

Episcopal deaconate on June 20, 1895, by

Bishop Leighton Coleman. George McGuire was

ordained to the Episcopal deaconate on June

29, 1896 by Bishop Boyd Vincent, and to the

Episcopal priesthood in 1897 by the same. (Bragg,

Rev. George F. (D.D.). Chapter XXXVI:

Negro Ordinations from 1866 to the Present.

In:

History of the Afro-American group of the

Episcopal church (1922). Baltimore,

Md.: Church Advocate Press, 1922. p.273.)

-

↑ In his quest to obtain valid

Apostolic Orders, Fr. McGuire had

himself re-ordained Bishop in the

American Catholic Church, being

consecrated on September 28, 1921, in

Chicago, Illinois, by Archbishop

Joseph René Vilatte, assisted by bishop

Carl A. Nybladh who had been consecrated by

Vilatte. However the

Orthodox Church considers Villate to be

an

Episcopi vagantes.

-

↑ These became the

Archdiocese of Kenya, and the

Archdiocese of Kampala and All Uganda.

-

↑ Orthodoxy in East Africa had a rather

unique origin as it was not the result of

missionary evangelism, nor was it originally

inspired by European/White introduction.

Orthodox Christianity was unlike all other

denominations, appealling to East Africans,

such as the

Kikuyus, especially because it was never

associated with racism, colonialism or

religious imperialism. (Metropolitan

Makarios (Tillyrides) of Kenya.

The Origin of Orthodoxy in East Africa.)

References

-

↑ Robert A. Hill, Marcus Garvey,

Universal Negro Improvement Association.

Letter Denouncing Marcus Garvey.

In:

The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro

Improvement Association Papers: 1826-August

1919. University of California

Press, 1983. pg.197.

-

↑

2.0

2.1

2.2

2.3

2.4

2.5

2.6

2.7 Mather, Frank Lincoln.

Who's Who of the Colored Race: A General

Biographical Dictionary of Men and Women

of African Descent. University

of Michigan. Gale Research Co., 1915.

pp.226-227.

-

↑

3.0

3.1 The Daily Gleaner.

West Africa. October 9, 1901.

p.7.

-

↑ The New York Times.

Bishop Coleman of Delaware Dies.

Sunday December 15, 1907. Page 13. (Obituary)

-

↑

5.0

5.1

5.2

5.3 White, Gavin. Patriarch

McGuire and the Episcopal Church. In:

Randall K. Burkett and Richard Newman (Eds.).

Black Apostles: Afro-American Clergy

Confront the Twentieth Century. G.

K. Hall, 1978. pp.151-180.

-

↑ Lumsden, Joy, MA (Cantab), PhD (UWI).

Father Raphael: His Background and

Career. September 29, 2007.

-

↑ The Daily Gleaner.

Port Maria: A Lecture. October

7, 1902. p.29.

-

↑ The Daily Gleaner.

Priest's Visit: Father Raphael of Greek

Orthodox Church: His Extensive Travels.

July 22, 1913.

-

↑

9.0

9.1

9.2 Fr. Oliver Herbel.

Morgan, Raphael.

The African American National Biography

at mywire.com. 1-Jan-2008.

-

↑

10.0

10.1

10.2

10.3 Manolis, Paul G.

Raphael (Robert) Morgan: The First Black

Orthodox Priest in America.

Theologia: Epistēmonikon Periodikon

Ekdidomenon Kata Trimēnian. (En

Athenais: Vraveion Akadēmias Athēnōn),

1981, vol.52, no.3, pp.464-480.

-

↑ Une Conquete du Patriarcat

Oecumenique. Echos d'Orient

. Vol. XI. No.68, 1908, pp.55-56.

-

↑ Lumsden, Joy.

Robert Josias Morgan, aka Father Raphael.

Jamaican History Month 2007.

February 16, 2007.

-

↑

13.0

13.1 Tony Martin.

McGuire, George Alexander.

Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance.

Volume 2. Cary D. Wintz, Paul Finkelman

(Eds.). Taylor & Francis, 2004. p.776.

-

↑ Fr. Oliver Herbel (AOC).

Jurisdictional Disunity and the Russian

Mission. Orthodox Christians

for Accountability.

April 22, 2009.

-

↑ The Jamaica Times.

Only Negro Who is a Greek Priest.

April 26, 1913.

-

↑ The Daily Gleaner.

Gives Lecture. Fr. Raphael Talks of His

Travels Abroad. August 15, 1913.

-

↑ Namee, Matthew.

The First Black Orthodox Priest in

America. OrthodoxHistory.org

(The Society for Orthodox Christian

History in the Americas). July 15, 2009.

External Links

Sources

Contemporary Sources

-

Bragg, Rev. George F. (D.D.). Chapter

XXXVI: Negro Ordinations from 1866 to the

Present. In:

History of the Afro-American group of the

Episcopal church (1922). Baltimore,

Md.: Church Advocate Press, 1922.

-

Bragg, Rev. George F. (D.D.). Afro-American

Clergy List. Priests. In:

Afro-American Church Work and Workers.

Baltimore, Md.: Church Advocate Print, 1904.

-

Hill,

Robert A., Marcus Garvey, Universal Negro

Improvement Association.

The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro

Improvement Association Papers: 1826-August

1919. University of California Press,

1983.

ISBN 9780520044562

-

Mather, Frank Lincoln.

Who's who of the Colored Race: A General

Biographical Dictionary of Men and Women of

African Descent. University of

Michigan. Gale Research Co., 1915.

-

The Daily Gleaner.

West Africa. October 9, 1901. p.7.

-

The Daily Gleaner.

Priest's Visit: Father Raphael of Greek

Orthodox Church: His Extensive Travels.

July 22, 1913.

-

The Daily Gleaner.

Gives Lecture. Fr. Raphael Talks of His

Travels Abroad. August 15, 1913.

-

The Daily Gleaner. November 2, 1914.

p.13.

-

The Jamaica Times.

Only Negro Who is a Greek Priest.

April 26, 1913.

-

Une Conquete du Patriarcat Oecumenique.

Echos d'Orient . Vol. XI.

No.68, 1908, pp.55-56.Publication of the

Roman Catholic Uniate Assumptionist Fathers,

located in Chalcedon)

-

Work, Monroe N., (Ed.). The Negro

Yearbook, an Annual Encyclopedia of the

Negro, 1921-1922. The Negro Year Book

Publishing Company:

Tuskegee Institute, 1922. (1921

edition)

Modern

Sources

-

Herbel, Fr. Oliver (OCA).

Jurisdictional Disunity and the Russian

Mission. Orthodox Christians for

Accountability.

April 22, 2009.

-

Herbel, Fr. Oliver (OCA).

Morgan, Raphael.

The African American National Biography

at mywire.com. 1-Jan-2008.

-

Herbel, Fr. Oliver (OCA).

Ph.D. Dissertation: “Turning to Tradition:

Intra-Christian Converts and the Making of

an American Orthodox Church,” 349 pp., under

the direction of Michael McClymond (2009).

-

Herbel, Fr. Oliver (OCA).

“The Relationship of the African Orthodox

Church to the Orthodox Churches and Its

Importance for Appreciating the Brotherhood

of St. Moses the Black,” Black Theology (forthcoming).

-

Joseph René Vilatte at Wikipedia.

-

Lumsden, Joy, MA (Cantab), PhD (UWI).

Father Raphael.

-

Lumsden, Joy.

Robert Josias Morgan, aka Father Raphael.

Jamaican History Month 2007. February

16, 2007.

-

Manolis, Paul G. Raphael (Robert) Morgan:

The First Black Orthodox Priest in America.

Theologia: Epistēmonikon Periodikon

Ekdidomenon Kata Trimēnian. (En Athenais:

Vraveion Akadēmias Athēnōn), 1981, vol.52,

no.3, pp.464-480. ISSN: 1105-154X

-

Martin, Tony.

McGuire, George Alexander.

Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance.

Volume 2. Cary D. Wintz, Paul Finkelman (Eds.).

Taylor & Francis, 2004.

-

Metropolitan

Makarios (Tillyrides) of Kenya.

The Origin of Orthodoxy in East Africa.

Orthodox Research Institute.

-

Namee, Matthew.

The First Black Orthodox Priest in America.

OrthodoxHistory.org (The Society for

Orthodox Christian History in the Americas).

July 15, 2009.

-

Namee, Matthew.

Fr. Raphael Morgan: America's First Black

Orthodox Priest. 16th Annual

Ancient Christianity & African-American

Conference. June 03, 2009.

-

Namee, Matthew. "Robert

Josias Morgan visits Russia, 1904."

OrthodoxHistory.org (The Society for

Orthodox Chrisitan History in the Americas).

September 15, 2009.

-

White, Gavin. Patriarch McGuire and the

Episcopal Church. In: Randall K. Burkett

and Richard Newman (Eds.). Black Apostles:

Afro-American Clergy Confront the Twentieth

Century. G. K. Hall, 1978. pp.151-180.

|