About fifteen years ago, I had a unique opportunity to visit

the hermitage of a Catholic priest-monk and theologian in the

mountains of Switzerland. He was well known for his writings on

the holy fathers of the early Christian Church, and no less well

known for his unusual—from the modern, Western point of

view—monastic lifestyle. Somewhat familiar with how Catholic

monasteries generally look today, I was not expecting to feel so

at home as an Orthodox monastic in his Catholic hermitage.

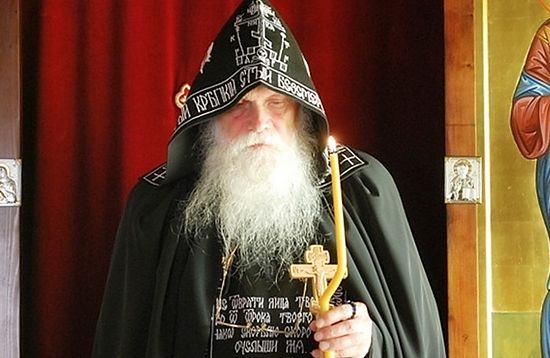

After ascending a wooded mountain path to a small dwelling

among the trees, we were greeted by an austere looking, elderly

man, his gray beard flowing over black robes. His head was

covered by a hood bearing a red cross embroidered over the

forehead. It was as if we had been transported to the Egyptian

desert, to behold St. Anthony the Great. As he and his

co-struggler Fr. Raphael treated us to tea, we talked about the

Church, East and West, and about the Russian Orthodox Church.

But there was no talk of them joining that Church—it would have

been uncomfortable to even mention it.

We felt that we had come into brief contact with a monk who

was one with us in spirit, although he was not in our Church,

and we parted with joy at this pleasant revelation while Fr.

Gabriel made the sign of the cross over us in the Orthodox

manner.

Fr. Gabriel never had and still does not have electronic

communication with the outside world, and we heard very little

from or about him after our visit. Nevertheless we did not

forget him, and in the intervening time we never ceased to think

how good it would be if he were in communion with us, the

Orthodox. But never would we have tried to approach this subject

with him—we somehow felt that God was guiding him as He sees

fit.

Fr. Raphael, a Swiss, has since passed away, and Fr. Gabriel

is the abbot and sole monk of what is now the Monastery of the

Holy Cross, part of the Russian Orthodox Church. He was baptized

Orthodox on the eve of the Dormition of the Theotokos in Moscow,

August 2010. He is now Schema-Archimandrite Gabriel.

Recently in Moscow on a very demanding schedule, Fr. Gabriel

still took the time to talk with us.

The Monastery of the Holy

Cross, Roveredo, Switzerland.

The Monastery of the Holy

Cross, Roveredo, Switzerland.

—Fr. Gabriel, although you have talked about your life in

other interviews, tell us again a little about yourself.

—I live in Roveredo, a tiny village of about 100 inhabitants. My

monastery is above the village in the woods, in the mountains of

the Lugano region, the Italian part of Switzerland.

—You had been Catholic from childhood?

—Yes, but not a practicing Catholic all my life. My father was

Lutheran, and my mother Catholic, and I was baptized Catholic.

But as it often happens in these cases, neither of my parents

practiced their religions. Neither my father nor mother went to

church. And so neither did I. But as young people always go

their own way, I rediscovered the faith of my Baptism. At first

I went to the Catholic Church, by myself. My parents did not

encourage me, they only tolerated this.

—Even your mother?

—She was a believing Catholic, but because of her marriage to a

Lutheran, she lost her practice. Only much later, when I was

already a monk, she went back to church and began to practice

her Catholic faith. My father grudgingly went with her, at least

on Easter or Christmas, because he did not want to spend the

holidays alone.

—Where were you born?

—Did these memories make you feel the desire to “fuse” Europe

back together with the Church of early Christianity?

—Of course, I did not know about the Orthodox Church for a long

time. I only discovered the existence of Orthodoxy

little-by-little. Some of my Orthodox friends of today have told

me that Catholics know that we “exist”, and nothing more. Simple

people even ask, “Do you venerate the Mother of God, too?” This

is even fifty years after Vatican II, which seemed to “open the

windows” of what was the very closed Catholic Church, and their

knowledge of Orthodoxy is still very poor. I had to discover

this little-by-little for myself. I did not know about any

Orthodox communities; there were no Orthodox churches in the

cities, because the Russians, at least, celebrated in Protestant

churches given them to use for a couple of hours on Sunday, as

is often the case even today. In Lugano, the Russian Orthodox

have bought a small Protestant church that was empty and unused.

All the other Orthodox communities, such as the Romanians,

celebrate in Catholic churches given them to use. But now we

have a little church, which must be paid for. It is gradually

being transformed into an Orthodox church, with an iconostasis

and everything.

So, I had to discover Orthodoxy little-by-little. When I was

about nineteen years old, after gymnasium, I

went with a friend to Rome, and there I discovered the early

Christian period: the catacombs, the old churches, those founded

by Sts. Constantine and Helen, and so on. It was very

impressive. I must confess that this strengthened my

consciousness of myself as a Catholic. Rome is apostolic

ground—here is the tomb of St. Peter, there of St. Paul, Santa

Maria Maggiore, Santa Croce, San Giovanni Laterana … all these

paleo-Christian churches, this incredible archeological

continuity. But it was much later that I discovered that

although there is continuity on the level of architecture, there

was no continuity on the level of the Apostolic Church, the

foundation.

I discovered only later that Santa Maria Maggiore and the other

churches have always been the same, but this continuity does not

exist on other levels, the more essential levels. It is the same

with the Anglicans. They have the Cathedral of St. Augustine in

Canterbury on one level, but on the theological level there is

no continuity, there is a break. However, at the time I was too

young to be aware that there are so many breaks and

interruptions in the history of the Western Church. I had to

discover this for myself, gradually.

People often ask me why I became Orthodox, and whether there was

a crucial moment or event in this evolution. There was a crucial

moment, and though I have said this before, I will repeat it. I

had to discover it—first on the literary level, through books,

music, etc. It is same for monasticism—I had to discover its

spirit through the writings of the desert fathers. But I

discovered real, living Orthodoxy at the age of twenty-one, when

I was in Greece. I was a student, not yet a monk. I could not

yet enter the monastery because my father wouldn’t allow it. I

was too young. I thank heaven that he did not allow it, because

that way I had an opportunity to travel to Greece with other

students, and to discover living Orthodoxy there. I saw holy

monasteries, and even met a holy monk. I went to the Liturgy.

This was before Vatican II. The Greeks were extremely kind and

friendly to me as a Catholic. Today that would probably be

different, because the Catholics have changed completely towards

the Orthodox.

—For the better, or for the worse?

—From the worst to the best. But now the Orthodox keep their

distance because they feel invaded.

I visited the seminaries and monasteries in Greece, and at one

time said to the monks and students, “Everything is fine here,

and I like it, but… it is a pity that you are separated from

us.” The immediate reply was, “You are wrong, it is you who

separated from us.” And so I was confronted for the first time

(I was only twenty-one years old) with this fundamental problem

of separation which is seen in a different way in the East and

West. Who is right? At twenty-one I didn’t have the means to

check the answer. Only little-by-little did I obtain them, and

so discovered that in fact it is the West that separated from

the common foundation. There is the archeological continuity, in

the famous churches from the time of Constantine and Helena for

example, but at the essential level— theology, Liturgics, and

everything else—there is not. My little book,

Earthen

Vessels,

speaks

about one little aspect that is very essential: that there was

an interruption.

—You mentioned before that you have read the book by the

German historian Johannes Haller about

the history of the Church up to the 1500s, as well as

other

books about the papacy, such as the one by Abbé Guettée.

—Yes, in fact I am reading the book by Haller now. It is purely

a history book, while the book by Guettée is polemics. You see,

Haller was impartial, very quiet, and he had free access to the

Vatican library. It is an objective history book, has very quiet

spirit, but is very powerful. The facts are overwhelming.

—You have said that you are glad you are reading about Church

history now, and not earlier, because it could have caused you

to lose your faith. Could you elaborate on that? You think you

needed to be stronger in order to face the facts. Is that

correct?

—I feel that faith in young people needs to be preserved,

protected. When you have a solid foundation, sufficient criteria

in your mind, and stronger faith, you will be able to judge.

—You mean a strong foundation in the Christian faith, and not

necessarily in the Roman Catholic faith? —Yes, then you can confront yourself with this mass of

historical facts.

—Because you feel that these facts taken by themselves may be

too devastating or scandalous for people?

—Yes, of course. You see, history is not theology. History is

just the facts—what happened. Haller’s work describes all the

ups and downs... it is fascinating, but it is true history. It

makes you wonder...

—History, warts and all?

—Yes, with all the warts; and the Pope’s claim of priority, of

being the head of the Church. It is very odd. In as early as the

fourth century, Pope Damasus claimed that the Roman Church (not

the Pope—yet) has primacy over all the other Churches, because

of what Jesus Christ said to Peter: “You are a rock, and upon

this rock I will build my Church” (cf. Mt. 16:8) So they, Rome,

have very much identified this rock with an institution, with

something visible—the Roman Church. Although very many fathers

of the Church, both East and West, identify this rock - as St.

Ambrose of Milan did in the year 382 - with the faith of the

people. It is the confession of Jesus Christ as the Son of the

Living God. It was not Peter’s personal faith; he was not a

better theologian or apostle than the other Apostles. It was

revealed to him by the Father. This is the rock which cannot be

destroyed. Peter shortly afterwards proves that he did not

understand anything of this confession. He is called a “devil”.

The Lord says, “Get thee behind me, satan” (cf. Mt. 16:23), and

so on. Not only St. Ambrose, but the most important fathers of

both the East and West also say the same thing. For the Roman

Catholic, it is absolutely obvious that this rock is the person

of Peter. And

Peter

(according to tradition) died in Rome, and

therefore it must be the Roman Church, and his successor, the

bishop of Rome, who is this rock. But Peter was in many places.

Why does it only have to be the place where he died? Many people

could claim to have his tomb... but he died in Rome, as did St.

Paul. But is this sufficient reason for this city, which was the

capital of the Roman Empire at the time, to become the head of

all the Churches, too? If there is any city that could lay claim

to that title it would be Jerusalem, the city where our Lord

died, and not Peter. In Jerusalem is the tomb of our Lord, and

there He resurrected. The head of the Church is in any case our

Lord.

—This always seemed to me to be a devastating example of what

is called in Russian плотское мудрование—fleshly

mindedness, a purely earthly way of thinking.

—Yes, and it immediately took hold. And what is so shocking in

this history of the papacy by Haller is precisely this worldly

aspect—how the spiritual means, such as excommunication and

interdict, have been used continuously, for hundreds of years,

just for political reasons. And what is even more shocking is

that people didn’t even bother to obey these interdicts. Whole

countries were under interdict; that means no Mass, no

Sacraments, no bells—nothing.

—Why?

—Why? Because the king would not give in to the Pope’s

territorial pretenses. The Pope was always fighting for his own

state, which became larger and larger, then smaller and smaller,

and still exists, as is the function in the Vatican City. It was

always for these political, territorial reasons. But most of

these countries, hundreds of kings, even bishops, simply didn’t

bother. They continued to celebrate mass, dispense the

Sacraments, and so on.

—So they were technically in “disobedience” to the Pope?

—Perfectly. To me, this was shocking. Even today it is shocking.

It is shocking that these spiritual means are used for purely

material, political reasons, and those who were hit by these

interdicts did not bother. So, you can imagine that this would

gradually destroy the Church from within. You understand much

better why Western Christianity destroyed and continues to

destroy itself from within. Not from outside. It is horrible, I

must say. It is what I call “secularization”. There are Popes

who themselves fought in battles. In was an ordinary thing for

Cardinals to have armies, and so on. This is secularization. It

means that the Church was closing its own horizon in on itself

to include increasingly secular interests. The Popes were

defending (understandably) their own independency—from the

Emperor, who they in fact needed, because without the Emperor

they would have no longer been independent of the dukes, the

king of Sicily, etc., whatsoever. You begin to understand a lot

of things.

—I assume you are reading this book in the original German.

Are there translations?

—This is a classic, but I don’t know—there are dozens of books

of this kind. I only quoted this book to tell you that even now,

afterwards, I am still interested in these questions, in reading

books that during my time of searching I was forbidden to read.

I don’t think that it would have been very useful to me then

anyway, because I would have completely lost my faith.

—Forbidden by whom?

—By my professors in the Catholic faculty in the university. In

Germany theology is taught by the state, and so I received my

theological education from a state university.

So, I continue to study just to deepen my understanding of the

reasons for the separation between East and West. Of course, you

can understand quite a lot from this, but there is still one big

mystery that I am still unable to understand: Why did God allow

this?

You can say that it was all the mistake of the Pope, but the

faithful had no choice. That is what I say to my friends now. I

say, “Look, you shouldn’t criticize or condemn Catholics. They

are just born on the wrong side of the street. It is not their

mistake. They have no choice. They never had any choice. The

whole West belonged to the Roman Patriarchate, which gradually

became larger and larger; they were not part of other

patriarchates. In any case, they are not today. That is their

mistake—they were just born there.

Fr. Gabriel Bunge in his

monastery in Switzerland.

Fr. Gabriel Bunge in his

monastery in Switzerland.

—This, however, brings to mind a question I always have. I

myself am a Westerner, a convert to Orthodoxy, I have no Eastern

Orthodox roots, and so my question is not intended to be

anti-Western. However, why are we apparently so prone to

earthly, secular thinking in the realm of religion—more than the

Christian East? Theoretically, the same process could have

happened anywhere.

—Theoretically, yes, but in practice, it did not. I think it is

because secularization is a very long process, and its clearest

expression is Protestantism, which is an inner-Catholic

phenomenon. It is an inner-Catholic phenomenon in the Western

Church which occurred after its separation from the Eastern part

of the Church. It could not develop before. I will tell you

about a most terrible experience. I am speaking about history,

but perhaps it is better to speak about my own “little history”

of seventy-three years. I entered the monastery at age

twenty-two in exactly the year that the Second Vatican Council

was opened. With my Greek Orthodox experience and so on, I

became a monk at Chevetogne, and

we were really full of hope that now the Roman Church would turn

back on its path, and there were many signs that this is how it

would happen. Paul VI had a very strong and deep desire for

reconciliation with the Orthodox Church. He was the incarnation

of this Janus-face (double-face) of the Western Church. On one

side, he wanted to concelebrate the Liturgy with Patriarch

Athenagoras when they met in Jerusalem, and he brought a golden

chalice to do so. But the ecumenists (thank God) separated these

two old men, because after such an act it would have become

worse than it was before. So, they did not serve together. He

offered to give the Patriarch that chalice. But it is well

proved that he wanted, through Liturgical reforms, to make the

Latin mass become acceptable to Protestants, not thinking, not

aware that it would in the same moment become completely

unacceptable to the Orthodox. You can see that the Catholic

Church is between these opposite positions—the Orthodox East and

the Protestant West. But then the general evolution did not go

towards the east, but towards the west. It became a slow self-Protestantization

of the Roman Church—a self-secularization, with all the

destruction, both physical and spiritual, that we have seen.

This was a real historical disaster of unseen dimensions. You

see, Protestantism is an inner-Catholic virus. And the Roman

Catholic Church has no antibody against that virus. The antibody

is Orthodoxy, which has never been, for five hundred years,

tempted by Protestantism. Even if there be an Ecumenical

Patriarch who has sympathies with Calvinism (as there once was),

this is local. It has no influence on the Orthodox

consciousness. It is just limited, and that is all. The Orthodox

Church had plenty of opportunities to be infected with

Protestantism and secularism, but they did not succumb—only on

the surface.

—A cold, rather than a cancer?

—Yes, a cold, not a cancer. This

is really a tragedy of historical dimensions.

Many Catholics are aware of this now, because they no longer

consider the Orthodox Church to be a competitor or adversary.

That is why they help them in any way to establish their

parishes in the West. They give them their churches so that they

can serve the Liturgies on Catholic altars, which would have

been unimaginable before.

—Just as an aside, last spring there was a delegation from

Russia present at a celebration in Sicily commemorating the aid

given by Russian soldiers to victims of the great Messina

earthquake in 1908. The Russian clergy present were invited to

serve the Liturgy for the local Orthodox congregation in the

Capella Palatina in Palermo.

—Ah, beautiful. The Russians continually celebrate solemn

Liturgies in the St. Nicholas Cathedral in Bari. I have seen one

Liturgy there celebrated by a Russian Metropolitan, about 20

priests, with a large choir. And I thought, “That is the Liturgy

required by this beautiful cathedral. But when it was over, the

Latin mass started… and you want to cry. You want to ask, “What

are you doing here?”

In a way, this is something out of the ordinary, but it shows

that many Catholics are not sure any more that they are right.

—Of those who are wavering—do you think they could go in the

direction of Orthodoxy, or might they instead give up everything?

—The only way I see it happening is if they turn to their own

Orthodoxy, because unless God works an unprecedented miracle

that turns everyone to Byzantine Orthodoxy, there is a whole

culture at work to prevent it. It is not just a matter of texts,

or formulas. But they must turn back to their own Orthodoxy,

their own traditions. For all these years, when I wrote my

little books, my aim was this: as a monk, to help people have a

spiritual life, to rediscover, reintegrate their own spiritual

heritage, which is of course the same as ours; because we have

the same roots. But the success of my endeavor, at least among

monks, is close to zero. Especially among monks. The books are

read mostly by laypeople, not by priests and monks. The monks

are the ones who practice yoga, Zen, reiki, and so on. When you

tell this to Russian monks they are shocked, they can’t imagine

this is happening. I do not judge them; thank God, it is our

Lord Who will judge the world and not me. But it means that

people are not looking for a solution, an answer within their

own tradition. They are looking outside of it, in non-Christian

religions. To me, Catholic monks practicing Zen meditation is

like Zen monks praying the Stations of the Cross. It is

completely absurd. In Buddhism, suffering has a different

origin; it is overcome in a different way from in Christianity.

There is no crucified Savior. Why should they meditate on the

Stations of the Cross? Of course, they do not.

—And how could a Christian monk, who believes in a personal

God, pray to the impersonal universe of Zen?

—In those monasteries they have Zen gardens... But could you

imagine the Stations of the Cross in a Zen monastery? Buddhist

monks kneeling before the Stations? It’s unimaginable.

—They have as if lost their self-identity.

—But what is so striking is they do not even try to dig in their

own ground, to find their own roots—the source, which has been

filled up by trash. They seem to be convinced that there is

nothing there, and never has been.

So we have to look for this source as well. I remember quite

well my monastic youth—there were those in the monastery who

felt that there was nothing there, that everything was dry. Then

came a Zen master, a Jesuit (very well-known; he died a long

time ago), and it was a revelation. At least it was something

spiritual... They had only seen formalism. Thanks to God, I had

discovered the holy fathers and the primitive monastic

literature before I came to the monastery. It was not the

monastery that taught me. I continued my search in the

monastery.

—In Chevetogne?

—Yes. I went there because it seemed closer to what I discovered

in Greece. To tell the truth, I was sent there. I had entered a

Benedictine Abbey in Germany. My novice master, the abbot, a

holy man, loved me very much, and he could see that I was not in

the right place. He sacrificed his promising novice and sent him

to Chevetogne, to see if this was more fitting. When I made my

monastic profession he came himself to visit me. He was a holy

man. My confessor, a Trappist monk, was also a holy man. I had

the chance to meet more than one holy man, even in the West.

They still exist.

I feel that my own path is to prove, even to the Orthodox, that

it is possible, even within the Western tradition, to rediscover

the common ground, and to live out of this. You can do this—not

by yourself, of course, but only with God’s grace. But then I

reached a point where I could no longer support being in only

spiritual communion with the Orthodox Church so close to my

heart. I wanted real, sacramental communion. Therefore, I asked

for it.

—Do you believe that on this path of digging down to the

roots of one’s own Western tradition, some would inevitably feel

compelled to take the step that you took?

—It is difficult to say, because it may not be technically

possible for everyone to do so. In the West, the Orthodox Church

had not been so well represented. Now it is changing. I have a

lot of friends who are following the same path, they are

“orthodox” but not in a confessional way. I do not know whether

they ever will become Orthodox. My own experience teaches me

that you will not always find help from the Orthodox side.

Proselytism is not normally Orthodox, and you will at times not

even find concrete help. I was even discouraged. There was a

well-known theologian (I will not say who)… I was a young

student, and he literally prohibited me and other monks from

Chevetogne to become Orthodox. He said, no! You shall not become

Orthodox! You must suffer in your flesh the tragedy of

separation. I did, because I had no other way. I addressed

another Russian Orthodox Metropolitan for help—he did not help

me. He just turned me away. And this was God’s will. In the

right moment, it truly went smoothly. Really. Like a letter in

the Swiss Post. But before, it seemed impossible.

—I am sure that everything happens according to God’s will

and plan, but do you feel that perhaps Orthodox people should

provide more encouragement to those people who are searching,

wavering? Who are digging deeply but not getting to the roots?

—They should know their own faith better, and be capable of

answering questions. They should not criticize everything and

everybody.

—As many converts are prone to do.

—Yes, the converts are the most severe judges. But, yes, they

should be able to answer essential questions. However, I am

speaking of my own experience, in Switzerland. I would suppose

that it is different in America, where there are hundreds of

different churches, Protestant denominations, and they are all

equal, so to say. There are dozens, unfortunately, of Orthodox

Churches also.

—Yes, America has the opposite problem: too much to choose

from.

—It is confusing.

—Even so, it is still hard for some Orthodox Americans to

come forth and say, “This is the true Church.”

—Nevertheless, it is easier in America because there is no

“dominant” Church. It is not as in Italy, Spain, or even in

Germany, where there are two dominant Churches, the Catholic and

the Protestant. Side-by-side, or one over the other, depending

upon how you see it, the Catholic Church is a dominant

confession. Any Orthodox activity would be received badly, I

suppose—all the more since they depend upon the good will of the

Catholic Church. To get a church, to celebrate, when you are too

poor to build your own church, you need the good will of the

Catholic bishops. But I think the situation in America is

different.

—Of course the Catholic Church is powerful in America, but in

North America they were initially entering into a Protestant,

Anglo-Saxon milieu. Nevertheless, the Catholic Church brought

many charitable works, hospitals, and schools to America,

although many people forget about this.

—Yes, but they should not.

Anyway, I am against any kind of proselytism, but we have to

answer questions, to say how things are, if people want to know.

God calls everybody to this, let’s say, “right place”.

Fr. Gabriel Bunge. Tonsure into the Great Schema.

Fr. Gabriel Bunge. Tonsure into the Great Schema.

—One last question. Do the local people who are not Orthodox

ever wander into your monastery and ask you about it?—The local population has known me for thirty years, but mine

was always a very specific monastic life; and because they do

not know monks, there are no

monks (there were Franciscan brothers there, who are not monks),

they always wondered what sort of brothers we were. We wore

black, we had beards, we used to wear hoods, and looked quite

old fashioned. Their own local saint from the fifth century also

dressed just as we did, but they do not know this anymore. They

knew that we were very close to the Christian Orient, the holy

fathers, and that what I am saying today is no different from

what I have always said. That is one thing that people noticed

when I became Orthodox. One lady, a simple housewife with no

university education, who knew that we became Orthodox, said, “I

just want you to know that you will always be our Father

Gabriel, and you are doing what you have always taught us to

do—to go back to our roots. The Orthodox Church is just as it

was in the beginning.” So, a simple person without any

theological studies can catch the sense of it. They were not

shocked. There was no opposition against us. It sometimes

happens, as we are walking in the streets, people will say,

“Father, may I ask you a question?” I say, okay. “Are you an

Orthodox monk?” I say, yes. “Bravo!”

They are not used to seeing monks anymore. The only monks they

see are Orthodox monks. The Franciscan friars wore lay clothing,

so unless you knew them personally, you would not know that they

were friars. But Orthodox monks are always to be identified as

such. And for these people, it isn’t a provocation. They feel

strengthened. They say, fine! Bravo!

I must say, I didn’t expect that reaction. When I was enthroned

as abbot of my monastery (a big word for a small reality), there

were several Catholics present, many of them Benedictine monks.

They asked if they could come; they wanted to be there. They

were present at the Orthodox Liturgy, and I presented them to

the Bishop, who received them amiably. It was not perceived as a

hostile act against them or against the Catholic Church, but

rather as the final consequence of what I had always taught.

—They could see your integrity in this.

—Many of them would even like to do the same thing, but they are

too bound to the world in which they live; or, their knowledge

of Orthodoxy, of the Apostolic tradition, is too poor.

So, we have to return to our roots.