I. IntroductionIt's that time of the year again: Christmas time! The trees, the lights, the stockings, the nativity scenes, and, of course, the giant inflatable Santas (really, what would Christmas be without them?) are going up all over the place. And, as every year, the same recycled and ridiculous historical inaccuracies are getting pushed on the unsuspecting masses. I've already seen the articles popping up online and being passed around by friends on Facebook; I'm sure that, as they always do, the National Geographic Channel and the History Channel have something "interesting" and uninformative in the works to deceive their viewers with as well. Search for "Christmas" in Google and immediately you are bombarded with the popular mythology about Christmas' origins. The History Channel's webpage on Christmas (the fourth on the list returned from my Google search), for example, erroneously claims, amongst other things, that Pope Julius I decided on a date of December 25 in order to replace the pagan festival of Saturnalia and that "the Greek and Russian orthodox [sic] churches" celebrate Christmas "13 days after the 25th, which is also referred to as the Epiphany or Three Kings Day."1

Before we begin looking at these trite claims in more detail, I want to point out explicitly that I am writing this post because of an interest in historical truth, not out of any desire to engage in apologetic. In spite of the claims of pseudo-Christian cults like the Jehovah's Witnesses, even if the date for Christmas had been based upon a pagan holiday (though this is not an admission that it was) originally on that date this would not impede or deligitimize the Christian celebration of the holiday. The days of the week all have pagan names (Wednesday, for instance, refers to the Norse god Woden) and yet I doubt I can find many of those who refuse to celebrate Christmas who also refuse to use the names of the days.2 Similarly, whether the Christmas tree or any of the other holiday accessories is of pagan origin or not is immaterial to the use of them by modern Christians; the toothbrush and toilet paper also have pagan origins and again I doubt that I could find many who refuse to use these items.3 The modern use of a Christmas tree no more implies an adherence to any of the pagan cults which used trees in their worship than the eating of a meal implies a dedication to the god Mithras whose worship involved the eating of communal meals.4

With all of that said, the purpose of this post is to clear away the dross of popular mythology and propaganda from the origins of Christmas and the various ways it is celebrated. We will first look at the origins of a Christian feast celebrating the birth of Christ and how that feast came to be placed on December 25. We will then look at some of the particular ways in which that feast is celebrated by Christians today, such as the display of Christmas trees, mistletoe, and nativity scenes, and search for their respective origins. Along the way, I will attempt to clear up some of the other common misconceptions about Christmas both ancient and modern, such as the already-quoted misunderstanding of the date of the celebration of Christmas by Orthodox Christians.

Since the discussion of the dating of Christmas will involve referencing several different calendars, I've color-coded all dates I mention in that section in order to avoid confusion. Dates in black refer to the Gregorian calendar, instituted by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 and today the common calendar of the West; dates in red refer to the Jewish calendar; dates in blue refer to the Julian calendar, instituted by Julius Caesar in 45 BCE and still in use in the majority of the Orthodox churches today;5 and dates in green refer to the Revised Julian calendar, adopted beginning in 1923 by a number of Orthodox churches.6

II. The myth and its source

The common mythology of Christmas origins goes something like this:7

Early Christians did not celebrate the birth of Christ and even regarded the celebration of birthdays, including even that of their savior, as a superstitious pagan practice. For this reason, no one was even remotely interested in finding out the day of Christ's birth.

In the early fourth century, Constantine the Great became the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity. As a result of his conversion, a number of innovations derived from paganism were introduced into Christian practice and belief, Christmas amongst them. The celebration of Christmas was introduced in order to make it easier for pagans to convert to Christianity as Christmas was intended as a Christianized version of the pagan feasts of Saturnalia and the birth celebrations of the pagan gods Sol Invictus and/or Mithras (which feast Christianity was intended to replace differs between individual myth-propagators). St. Julius I, who was Bishop (it is anachronistic to call him "Pope" although most myth-propagators do) of Rome in the years 337-352 CE, is most often named as the culprit in the crime of transplanting the December 25th holiday from paganism to Christianity.

Not only were the holiday and its date brought over from paganism, according to the myth-propagators, but so were most of the elements of the celebration surrounding it. Santa Claus is a Christianization of any number of pagan deities (again, it depends upon the preference of the individual myth-propagator), sometimes even of Satan -- the evil one! -- himself. The Christmas tree comes from Germanic winter celebrations. The gift-giving comes from Roman Saturnalia celebrations. And so on the myths go.

The problem with all of this is that it is, to be entirely frank, a big bag of worthless excrement.

If the popular conception that Christmas is of pagan origin is incorrect, some may ask, where did it come from and how did it become such a widespread belief? Like the myth of the so-called "Dark Ages," the source of the mythology surrounding Christmas is the anti-Papist and, later, anti-Christian propaganda of the Protestant Reformation and the Enlightenment. There are in particular two individuals to blame for the invention of the myths.

In 1743, a German Protestant named Paul Ernst Jablonski, in an effort to discredit the Roman Catholic Church, claimed that the celebration of Christmas was one of the numerous "paganizations" of Christianity which had occurred in the fourth century.8 His grand thesis was that paganizations like the adoption of Christmas had degenerated Christianity from its original purity and led to the creation of the Roman Catholic Church.

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Dom Jean Hardouin, himself a Roman Catholic monk, in an attempt to counter the claims of Protestants that the Roman Catholic Church was the result of paganization of Christianity, unintentionally contributed to the myths about Christmas.9 He attempted, in his writings on the subject, to demonstrate that the Roman Church had adopted pagan festivals and Christianized them without corrupting the Christian gospel.

Those modern myth-propagators who do actually reference sources (that there are so few who do should tell us something about their truthfulness and scholarly nature -- or, more precisely, lack thereof) generally cite Jablonski and Hardouin prolifically.III. It's beginning to look a lot like Christmas

The first question that we'll look at is when celebrations of Christmas began. Was it really in the middle to late fourth century and are Constantine and Julius really the originators? The answer to these questions is no, no, and no.

While pinning down the earliest celebration of a holiday commemorating the birth of Christ is a difficult if not impossible task, it is undoubtedly clear that such a celebration came about very early.

Already by the end of the first century and beginning of the second, Christians had developed what appears to have been a near-obsession with the story of the birth and childhood of Christ. This concern is evident in such writings as the Infancy Gospel of James and the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, both written some time in the middle of the second century. These works and others like them seem to have been written with a focus on emphasizing the humanity of Christ against certain heretical groups, such as the docetists and, later, the Gnostics and the Marcionites, who denied the humanity of Christ and claimed instead that he was actually solely divine and only appeared to be human. To counter these heretical claims, the Orthodox placed a special emphasis on the human conception and birth of Christ from the Virgin Mary. There is, however, no explicit mention of a celebration of these events. Equally, there is also no condemnation of nor aversion to such a celebration.

Too much has been made by Christmas' modern detractors of Origen of Alexandria's rejection of the celebration of birthdays.10 Although he doesn't mention the birth of Christ specifically, it is assumed that since he seems to have rejected the celebration of birthdays in general as a pagan practice he also would have rejected the celebration of a holiday commemorating Christ's birth. This may or may not be true, but the reality is that Origen's testimony doesn't matter much to the issue. Origen espoused a number of heretical beliefs, due to his acceptance of Platonic influences, which ran contrary to traditional Christian teaching, including universal salvation, the pre-existence of souls, and a rejection of material creation as a by-product of the Fall.11 For holding and teaching these and other heretical ideas, he was condemned by several Christian bishops in his own lifetime and afterward; these condemnations culminated in an official anathema against him by the Fifth Ecumenical Council (Second Council of Constantinople) in 553 CE.12 In short, Origen cannot be counted on to accurately convey the consensus of Christians of his time or any other.

Turning to more accepted and accurate primary sources of Christianity's early centuries, however, we find some decent indicators of the ancientness of an annual celebration of Christ's birth, although the references are a bit patchwork and often lack details in content. A few examples:

The earliest mention of such a feast comes from St. Hippolytus of Rome's Commentary on Daniel, written in about 202 AD; I will discuss this particular passage a bit more in depth in the next section.

St. John Chrysostom, in his homily delivered in Antioch in 386 AD, says that the celebration of a feast on the birth of Christ is an ancient tradition.13

The Philokalian Calendar, a calendar of Christian feasts compiled in Rome in 354 AD, lists Christmas as an established feast of the Church.14

The Apostolic Constitutions, a collection of earlier Christian canons, at least a portion of which probably date from the Apostles, compiled probably in the years 375-380 AD, demands that Christians celebrate Christmas and ostensibly attributes this demand to the Apostles.15

In 302 AD in Nicomedia, one of the regions hardest hit by the persecutions of Christians ordered by the Emperor Diocletian, a number of ancient sources record that a large group of Christians were shut inside their church and then burnt alive while celebrating Christmas services.16 The usual number listed is 20,000 but such a number seems exaggerated; it is more likely than 20,000 is the total number of Christians martyred in Nicomedia during the persecution and that a significant portion of those were killed in the massacre on Christmas.

The heretical sect from the Donatists broke from the Orthodox Church in about 312 AD; they zealously, even legalistically, clung to Christian faith and practice exactly as it had been at that moment in time in North Africa and they rejected any further development as innovation and heresy. Significantly, it was recorded by St. Augustine of Hippo in about 400 AD that the Donatists celebrated Christmas.17

In the middle of the fourth century, St. Ephraim of Syria wrote a series of lengthy liturgical hymns for use during a celebration of the birth of Christ. 18

IV. Calculating Christmas, or How the Church got December from March and April

The common contention that December 25 was instituted in order to replace a pagan holiday already on that date falls apart very quickly in the light of the overwhelmingly evidence that there was no pagan holiday on that date. The contention relies upon the fallacy, still common in neo-pagan and pseudo-Christian circles, that anything pagan must necessarily precede anything Christian chronologically. On the contrary, already in its first two centuries of existence Christianity had exerted a powerful influence on contemporary pagan belief and practice.19 In the second through fifth centuries, there were a number of innovations in Greco-Roman pagan religion and philosophy that were inspired by contact with Christianity.

The earliest historical source that exists which places a pagan holiday on December 25 is the proclamation by Roman Emperor Aurelian of a celebration of Sol Invictus on that day in 274 AD.20 The earliest Christian reference to December 25 as the birth of Christ, however, dates from 202 AD. In that year, St. Hippolytus of Rome wrote in his Commentary on Daniel:

For the first advent of our Lord in the flesh, when he was born in Bethlehem, eight days before the kalends of January [December 25th], the 4th day of the week [Wednesday], while Augustus was in his forty-second year, [2 or 3BC] but from Adam five thousand and five hundred years. He suffered in the thirty third year, 8 days before the calends of April [March 25th], the Day of Preparation, the fifteenth year of Tiberius Caesar [29 or 30 AD], while Rufus and Roubellion and Gaius Caesar, for the 4th time, and Gaius Cestius Saturninus were Consuls.21

Given that Aurelian's religious reforms, like those of Julian the Apostate a century later, seem largely to have been an attempt to undermine Christianity by introducing popular elements of it into paganism, thereby theoretically making paganism more attractive, it seems far more probable that Aurelian's institution of a celebration of Sol Invictus on December 25 was an attempt to usurp a Christian holiday already established and widely celebrated on that date, rather than the reverse.

If they didn't get the idea from the pagans, then how did Christians decide on December 25 as the date to celebrate the birth of Christ? Interestingly, the settling of that commemoration on December 25 actually had more to do with Christ's death than with his birth!

A primary concern amongst early Christians was establishing an accurate and uniform date for the celebration of Pascha.22 Various formulas and historical sources were put forward by early Christians in their attempts to achieve this goal. By the third century, two dates had emerged as standard among Christians; in the West 25 March (you may have noted this date in the quote above from St. Hippolytus of Rome) became the standard date for Christ's death and in the East Christians believed Christ to have died on 6 April.23

Drawing upon an ancient Jewish tradition that holds that a prophet enters life (that is, is conceived) and leaves it (that is, dies) on the same day, Christians concluded that Christ must have also been conceived on 25 March or 6 April (depending upon which date was held to).24 Exactly nine months (the duration of a "perfect" human pregnancy) after 25 March is 25 December; exactly nine months after 6 April is 6 January. As a result, Christians came to commemorate Christ's birth on these two dates; in the West the former was celebrated and in the East the latter.

V. Conception, Birth, and Baptism then and now

During the fourth and fifth centuries, a gradual and natural compromise was reached between these two close but differing conclusions. 25 December became the nearly universally accepted date for the commemoration of Christ's birth (in other words, Christmas) and 25 March was universally celebrated as the date of Christ's conception. 6 January became identified, especially in the East, with Christ's baptism, as St. Luke seems to indicate in his gospel that Christ was baptized on his 30th birthday.25

25 March, commonly referred to as "Annunciation," is still celebrated by most Christians as the day that the Angel Gabriel visited the Virgin Mary and proclaimed that she had conceived by the Holy Spirit.26 6 January, usually called either "Epiphany" or "Theophany," is celebrated by Orthodox Christians and other Eastern Christians as the day of Christ's baptism and by Roman Catholics and some other Western Christians as the day the magi visited the Christ child.27 And, of course, 25 December is still celebrated by almost all Christians as the Feast of the Nativity in the Flesh of our Lord, God, and Savior Jesus Christ, commonly called "Christmas." The only exception (aside, of course, from those pseudo-Christians who ignorantly reject Christmas altogether) is the Armenian Apostolic Church, the ancient Christian church of Armenia, which continues to celebrate both the birth and the baptism of Christ on 6 January (19 January on the Gregorian calendar).

A common but erroneous claim is the one I cited earlier from the History Channel's web page on Christmas that Orthodox Christians celebrate Christmas "13 days after the 25th, which is also referred to as the Epiphany or Three Kings Day." Most Orthodox Christians celebrate Christmas on 7 January (according to the Gregorian calendar); this is, however, 25 December on the Julian calendar. In 1582, the Roman Catholic Pope reformed the calendar used by Western Christians. This calendar, called the "Gregorian calendar," became the standard calendar of the West and today is the common calendar of the world. The Julian calendar, used by most Orthodox Christians, is currently 13 days behind the Gregorian calendar. The Orthodox celebration of Christmas on 7 January has absolutely nothing to do with Epiphany or Three Kings (which falls on 6 January and so, for those Orthodox who use the Julian calendar, on 19 January according to the Gregorian). It should also be noted that a sizable minority of Orthodox Christians use what is called the Revised Julian calendar, which calendar is currently in sync with the Gregorian calendar, and so celebrate Christmas on 25 December right alongside Western Christians.

To summarize: Even though Western Christians celebrate Christmas on 25 December and most Orthodox Christians celebrate it on 7 January (which is also 25 December) and some Orthodox Christians celebrate it on 25 December, all Christians (except the Armenians!) celebrate Christmas on 25 December. Complicated stuff? Yeah, a little...

VI. Santa Claus is coming to town

Now that we've addressed and dismissed the mythology surrounding the celebration and dating of Christ's birth, let's briefly take a look at the origins of some other Christmas-related items:

Santa Claus. Contrary to the claims of some horribly misinformed (or uninformed) individuals,28 Santa Claus is real and is not a distraction from the real meaning of Christmas. Santa Claus, whose real name is St. Nicholas of Myra, was an Orthodox Christian bishop in Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey) in the fourth century. He suffered for Christ under the persecution of Diocletian and is remembered even today by Orthodox Christians for his charitable, compassionate, and Christlike life. To read more about St. Nicholas, go here. And, if you've ever wondered why Santa Claus looks the way he does, take a look at some Orthodox bishops.

Gift-giving. The gift-giving on Christmas is done in imitation of St. Nicholas and of the gifts the magi presented to Christ; the practice dates to perhaps the fifth century.

Stockings. The hanging of stockings over the fireplace is derived from one of the stories of the activities of St. Nicholas in which he left several gold coins in the stockings, hung over the mantle to dry, of several poor young girls who were in desperate need of money.

Christmas trees. Contrary to popular belief, the origins of the Christmas tree are relatively modern and are unrelated to ancient pagan practices.29 The trees were originally used, decorated with hanging apples, in plays presented in Germany on Christmas eve in the late Middle Ages. The practice was brought to America by German immigrants in the 18th century and has remained a staple of American Christmas tradition since.

12 days of Christmas. The often misunderstood 12 days of Christmas are the 12 days from the Nativity of Christ on 25 December to the baptism of Christ on 6 January. The 12 day period between these two feast days is a period in which Christians traditionally abstain from fasting (traditionally, Christians fast for four weeks [in the Western tradition] or 40 days [in the Eastern tradition] before Christmas) and instead feast and enjoy good times with family and friends.

Yule log. The burning of the Yule log is another aspect of the modern Christian celebration which has falsely been lampooned as of ancient pagan origin but is actually of modern Christian origin.30 The burning of the yule log became popular beginning in the late 16th century in England.

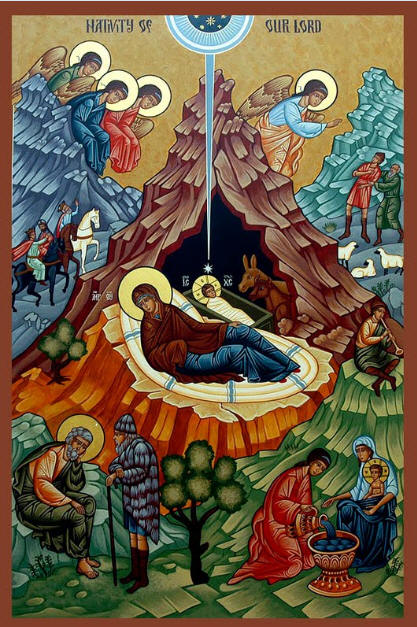

Nativity scene. The display of a Nativity scene, commonly called a "creche," was popularized by Francis of Assisi, a Roman Catholic saint, beginning in 1223.

Caroling. Caroling door-to-door began in the late Middle Ages as a development from the earlier Christian practice of singing hymns and performing liturgical dramas on Christmas eve.

Mistletoe. The tradition of kissing under the mistletoe is of unknown origin. The supposed link between the modern practice and the story of the pagan god Baldr is tenuous at best and entirely conjectural.

Christ is Born!

Glorify Him!

Notes

1. "Christmas -- History.com Articles, Video, Pictures and Facts" (2010) http://www.history.com/topics/christmas (Retrieved 3 December 2010).

2. "The Days of the Week" (2005) http://www.friesian.com/week.htm (Retrieved 3 December 2010). Interestingly, early Quakers did indeed refuse to use the names of the days of the week for this very reason. See David Yount, How the Quakers Invented America(Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2007), 11.

3. On the origins of the toothbrush see "Who invented the toothbrush and when was it? (Everyday Mysteries: Fun Science Facts from the Library of Congress" (23 August 2010) http://www.loc.gov/rr/scitech/mysteries/tooth.html (Retrieved 3 December 2010). On the origins of toilet paper see "History Of Toilet Paper" (2009) http://www.toiletpaperhistory.net/toilet-paper-history/history-of-toilet-paper/ (Retrieved 3 December 2010).

4. Manfred Clauss, The Roman Cult of Mithras: The God and His Mysteries(New York: Routledge, 2001), 113.

5. For basic information on the Gregorian, Julian, and Jewish calendars as well as other calendars and an useful date converter see "Calendar Converter" (November 2009) http://www.fourmilab.ch/documents/calendar/ (Retrieved 3 December 2010). Thanks to my brother Andrew Walker for tracking that great tool down for this essay.

6. For some basic information on the Revised Julian calendar see "Revised Julian Calendar -- OrthodoxWiki" (21 April 2010) http://orthodoxwiki.org/Revised_Julian_Calendar (Retrieved 3 December 2010).

7. The myths differ in some ways amongst their various propagators; I offer here a basic summary of the most popular elements. To read some of these myths in their most recent form as stated by their modern adherents, see, for example, the page from the History Channel's website already cited; Kelly Wittmann, "Christmas' pagans origins" (2002) http://www.essortment.com/all/christmaspagan_rece.htm (Retrieved 4 December 2010); "Take Your Stand for True Worship - Jehovah's Witnesses Official Website" (2009) http://www.watchtower.org/e/bh/article_16.htm (Retrieved 4 December 2010); and David C. Pack, "The True Origin of Christmas" (2005) http://www.thercg.org/books/ttooc.html (Retrieved 4 December 2010).

8. William J. Tighe, "Calculating Christmas" (December 2003) http://www.touchstonemag.com/archives/article.php?id=16-10-012-v (Retrieved 4 December 2010).

9. ibid.

10. Origen of Alexandria, Homily on Leviticus, 8.

11. , "Origen and Origenism" in The Catholic Encyclopedia (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911). Retrieved 4 December 2010 from New Advent: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11306b.htm

12. "5th Ecumenical Council (2nd Constantinople) - Anathemas against Origen" (553) http://www.comparativereligion.com/anathemas.html (Retrieved 4 December 2010).

13. Fr. John A. Peck, "The Ancient Feast of Christmas | Preachers Institute" (2 December 2010) http://preachersinstitute.com/2010/12/02/the-ancient-feast-of-christmas/ (Retrieved 4 December 2010).

14. Roger Pearse, "The Chronography of 354 AD. Part 6: the calendar of Philocalus. Inscriptiones Latinae Antiquissimae, Berlin (1893) pp.256-278" (2006) http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/chronography_of_354_06_calendar.htm (Retrieved 4 December 2010).

15. Apostolic Constitutions, Book V, Section III.

16. "20,000 Martyrs of Nicomedia" (2008) http://ocafs.oca.org/FeastSaintsViewer.asp?SID=4&ID=1&FSID=103664 (Retrieved 4 December 2010).

17. Andrew McGowan, "How December 25 Became Christmas" (2010) http://www.bib-arch.org/e-features/christmas.asp (Retrieved 4 December 2010).

18. J.B. Morris and A. Edward Johnston, translators, "Nineteen Hymns on the Nativity of Christ in the Flesh" (13 July 2005) http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf213.iii.v.i.html (Retrieved 4 December 2010).

19. Arnaldo Momigliano, On Pagans, Jews, and Christians(Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1987).

20. Christian Körner, "Roman Emperors - DIR Aurelian" (2001) http://www.roman-emperors.org/aurelian.htm (Retrieved 4 December 2010).

21. Tom C. Schmidt, "Hippolytus and December 25th, the birthday of Christ-Christmas" (8 December 2009) http://chronicon.net/blog/chronology/hippolytus-and-december-25th-the-birthday-of-christ/ (Retrieved 4 December 2010). It should be noted that this portion of Hippolytus' work was long thought interpolated, forged, or irreparably damaged due to apparent contradictions with other works of Hippolytus and a problematic manuscript tradition. Both issues have, however, been resolved. On the former, see Tom C. Schmidt, "Hippolytus and the Original Date of Christmas" (21 November 2010) http://chronicon.net/blog/chronology/hippolytus-and-the-original-date-of-christmas/ (Retrieved 4 December 2010). On the latter, see Roger Pearse, "The text tradition of Hippolytus 'Commentary on Daniel'" (12 January 2010) http://www.roger-pearse.com/weblog/?p=3343 (Retrieved 4 December 2010).

22. Pascha, Greek for "Passover," is the more ancient and appropriate name for the feast commonly called "Easter" amongst Western Christians; it is the celebration of the Resurrection of Christ. The controversy concerning the date for celebrating Pascha was perhaps most explicitly played out in the Quartodeciman controversy of the second through fourth centuries in which Western Christians and the Christians of Asia Minor argued over whether Christ's death should be marked on 14 Nisan (the date of Christ's death on the Jewish calendar) or Christ's death should be remember on the Friday following 14 Nisan so that Pascha should always fall on a Sunday. Eventually, it was decided that the Christian Church should renounce the use of the Jewish calendar altogether in order to avoid a reliance on rabbis who had rejected Christ and that Pascha should always be kept on a Sunday.

23. Tighe, "Calculating."

24. McGowan, "How December."

25. Luke 3:23 states that Christ had then began to be 30 years old. On what other day, early Christians asked, can someone begin to be a certain age but on their birthday?

26. "The Annunciation of our Most Holy Lady, the Theotokos and Ever-Virgin Mary" (2005) http://ocafs.oca.org/FeastSaintsViewer.asp?SID=4&ID=1&FSID=100884 (Retrieved 5 December 2010).

27. "Feast of the Theophany of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ" (2005) http://ocafs.oca.org/FeastSaintsViewer.asp?SID=4&ID=1&FSID=100106 (Retrieved 5 December 2010).

28. For example, see "Why A Local Pastor Is On Santa's Naughty List" (2 December 2010) http://www.q13fox.com/news/kcpq-local-pastor-spoils-christmas-120210,0,1516784.story (Retrieved 5 December 2010).

29. Daniel Daly, "MYSTAGOGY: In Defense of the Christmas Tree" (20 December 2009) http://www.johnsanidopoulos.com/2009/12/in-defense-of-christmas-tree.html (Retrieved 5 December 2010).

30. "CNP Articles - Christmas (Part VI)" (1911) http://www.canticanova.com/articles/xmas/art346.htm (Retrieved 5 December 2010).