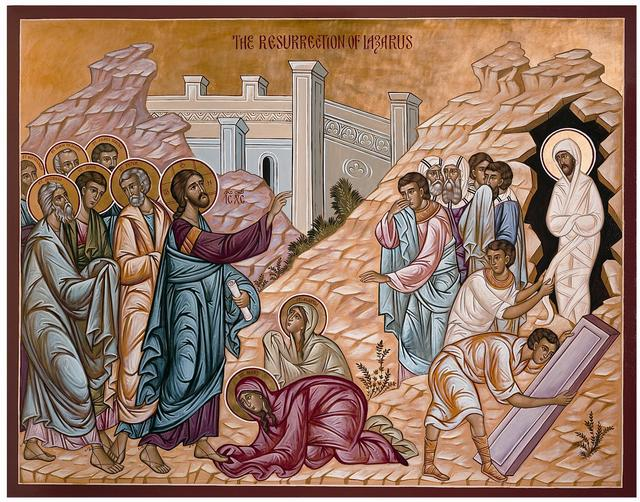

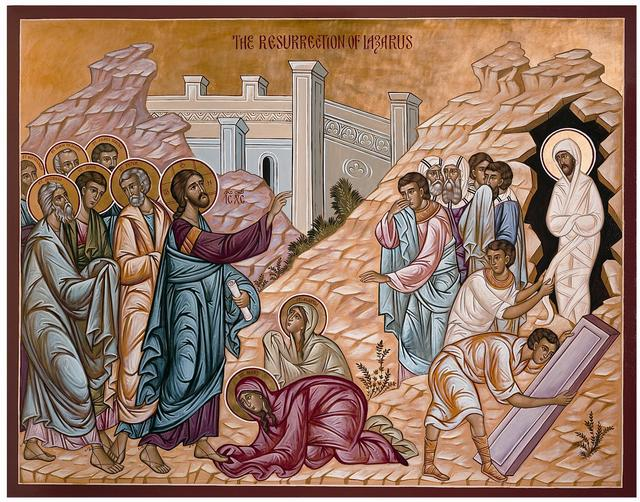

Largely ignored by much of Christendom, the Orthodox mark the day

before Palm Sunday as “Lazarus Saturday” in something of a prequel

to the following weekend’s Pascha. It is, indeed a little Pascha

just before the greater one. And this, of course, was arranged by

Christ Himself, who raised His friend Lazarus from the dead as

something of a last action before entering Jerusalem and beginning

His slow ascent to Golgotha through the days of Holy week.

One of the hymns of the Vigil of Lazarus Saturday says that Christ

“stole him from among the dead.” I rather like the phrase. Next

weekend there will be no stealing, but a blasting of the gates of

hell itself. What he does for Lazarus he will do for all.

Lazarus, of course, is different from those previously raised from

the dead by Christ (such as the daughter of Jairus). Lazarus had

been four days dead and corruption of the body had already set in.

“My Lord, he stinks!” one of his sisters explained when Christ

requested to be shown to the tomb.

I sat in that tomb in September 2008. It is not particularly notable

as a shrine. It is today, in the possession of a private, Muslim

family. You pay to get in. Several of our pilgrims did not want to

pay to go in. I could not stop myself.

Lazarus is an important character in 19th century Russian

literature. Raskolnikov, in Crime

and Punishment, finds the beginning of his repentance of the

crime of murder, by listening to a reading of the story of Lazarus.

It is, for many, and properly so, a reminder of the universal

resurrection. What Christ has done for Lazarus He will do for all.

For me, he is also a sign of the universal entombment: that even

before we die, we have frequently begun to inhabit our tombs. We

live our life with the doors closed (and we stink). Our hearts are

often places of corruption and not the habitation of the good God.

Or, at best, we ask Him to visit us as He visited Lazarus. That

visit brought tears to the eyes of Christ. The state of our

corruption makes Him weep. It is such a contradiction to the will of

God. We were not created for the tomb.

I also note that in the story of Lazarus – even in his being raised

from the dead – he rises in weakness. He remains bound by his

graveclothes. Someone must “unbind” him. We ourselves, having been

plunged into the waters of Baptism and robed with the righteousness

of Christ, too often exchange those glorious robes for graveclothes.

Christ has made us alive, be we remain bound like dead men.

I sat in the tomb of Lazarus because it seemed so familiar. But

there is voice that calls us all.